Windows Pointing Device Support in Firefox

Introduction

This document is intended to provide the reader with a quick primer and/or refresher on pointing devices and the various operating system APIs, user experience guidelines, and Web standards that contribute to the way Firefox handles input devices on Microsoft Windows.

The documentation for these things is scattered across the web and has varying levels of detail and completeness; some of it is missing or ambiguous and was only determined experimentally or by reading about other people’s experiences through forum posts. An explicit goal of this document is to gather this information into a cohesive picture.

We will then discuss the ways in which Firefox currently (as of early 2023) produces incorrect or suboptimal behavior when implementing those standards and guidelines.

Finally, we will raise some thoughts and questions to spark discussion on how we might improve the situation and handle corner cases. Some of these issues are intrinsically “opinion based” or “policy based”, so clear direction on these is desirable before engineering effort is invested into reimplementation.

Motivation

A quick look at the pile of defects on bugzilla.mozilla.org marked with [win:touch] will show anyone that Firefox’s input stack for pointer devices has issues, but the bugs recorded there don’t begin to capture the full range of unreported glitches and difficult-to-reproduce hiccups that users run into while using touchscreen hardware and pen digitizers on Firefox, nor does it capture the ways that Firefox misbehaves according to various W3C standards that are (luckily) either rarely used or worked around in web apps (and thus go undetected or unreported).

These bugs primarily manifest in a few ways that will each be discussed in their own section:

Firefox failing to return the proper values for the

pointer,any-pointer,hover, andany-hoverCSS Media QueriesFirefox failing to fire the correct pointer-related DOM events at the correct time (or at all)

Firefox’s inconsistent handling of touch-related gestures like scrolling, where certain machines (like the Surface Pro) fail to meet the expected behavior of scrolling inertia and overscroll. This leads to a weird touch experience where the page comes to a choppy, dead-stop when using single-finger scrolling

It’s worth noting that Firefox is not alone in having these types of issues, and that handling input devices is a notoriously difficult task for many applications; even a substantial amount of Microsoft’s own software has trouble navigating this minefield on their own Microsoft Surface devices. Defects are instigated by a combination of the intrinsic complexity of the problem domain and the accidential complexity introduced by device vendors and Windows itself.

The intrinsic complexity comes from the simple fact that human-machine interaction is difficult. A person must attempt to convey complex and abstract goals through a series of simple movements involving a few pieces of physical hardware. The devices can send signals that are unclear or even contradictory, and the software must decide how to handle this.

As a trivial example, every software engineer that’s ever written page scrolling logic has to answer the question, “What should my program do if the user hits ‘Page Up’ and ‘Page Down’ at the same time?”. While it may seem obvious that the answer is “Do nothing.”, naively-written keyboard input logic might assume the two are mutually-exclusive and only process whichever key is handled first in program order.

Occasionally, a new device will be invented that doesn’t obviously map to existing abstractions and input pipelines. There will be a period of time where applications will want to support the new device, but it won’t be well understood by either the application developers nor the device vendor themselves what ideal integration would look like. The new Apple Vision VR headset is such a device; traditional VR headsets have used controllers to point at things, but Apple insists that the entire thing should be done using only hand tracking and eye tracking. Developers of VR video games and other apps (like Firefox) will inevitably make many mistakes on the road to supporting this new headset.

A major source of defect-causing accidental complexity is the lack of clear expectations and documentation from Microsoft for apps (like Firefox) that are not using their Universal Windows Platform (UWP). The Microsoft Developer Network (MSDN) mentions concepts like inertia, overscroll, elastic bounce, single-finger panning, etc., but the solution is presented in the context of UWP, and the solution for non-UWP apps is either unclear or undocumented.

Adding to this complexity is the fact that Windows itself has gone through several iterations of input APIs for different classes of devices, and these APIs interact with each other in ways that are surprising or unintuitive. Again, the advice given on MSDN pertains to UWP apps, and the documentation about the newer “pointer” based window messages is a mix of incomplete and inaccurate.

Finally, individual input devices have bugs in their driver software that would disrupt even applications that are using the Windows input APIs perfectly. Handling all of these deviations is impossible and would result in fragile, unmaintainable code, but Firefox inevitably has to work around common ones to avoid alienating large portions of the userbase.

Technical Background

A Quick Primer on Pointing Devices

Traditionally, web browsers were designed to accommodate computer mice and devices that behave in a similar way, like trackballs and touchpads on laptops. Generally, it was assumed that there would be one such device attached to the computer, and it would be used to control a hovering “cursor” whose movements would be changed by relative movement of the physical input device.

However, modern computers can be controlled using a variety of different pointing devices, all with different characteristics. Many allow multiple concurrent targets to be pointed at and have multiple sensors, buttons, and other actuators.

For example, the screen of the Microsoft Surface Pro has dual capabilities of being a touch sensor and a digitizer for a tablet pen. When being used as a workstation, it’s not uncommon for a user to also connect the “keyboard + touchpad” cover and a mouse (via USB or Bluetooth) to provide the more productivity-oriented “keyboard and mouse” setup. In that configuration, there are 4 pointer devices connected to the machine simultaneously: a touch screen, a pen digitizer, a touchpad, and a mouse.

The next section will give a quick overview of common pointing devices. Many will be familiar to the reader, but they are still mentioned to establish common terminology and to avoid making assumptions about familiarity with every input device.

Common Pointing Devices

Here are some descriptions of a few pointing device types that demonstrate the diversity of hardware:

Touchscreen

A touchscreen is a computer display that is able to sense the location of (possibly-multiple) fingers (or stylus) making contact with its surface. Software can then respond to the touches by changing the displayed objects quickly, giving the user a sense of actually physically manipulating them on screen with their hands.

Digitizing Tablet + Pen Stylus

These advanced pointing devices tend to exist in two forms: as an external sensing “pad” that can be plugged into a computer and sits on a desk or in someone’s lap, or as a sensor built right into a computer display. Both use a “stylus”, which is a pen-shaped electronic device that is detectable by the surface. Common features include the ability to distinguish proximity to the surface (“hovering”) versus actual contact, pressure sensitivity, angle/tilt detection, multiple “ends” such as a tip and an eraser, and one-or-more buttons/switch actuators.

Joystick/Pointer Stick

Pointer sticks are most often seen in laptop computers made by IBM/Lenovo, where they exist as a little red nub located between the G, H, and B keys on a standard QWERTY keyboard. They function similarly to the analog sticks on a game controller – The user displaces the stick from its center position, and that is interpreted as a relative direction to move the on-screen cursor. A greater displacement from center is interpreted as increased velocity of movement.

Touchpad

A touchpad is a rectangular surface (often found on laptop computers) that detects touch and motion of a finger and moves an on-screen cursor relative to the motion. Modern touchpads often support multiple touches simultaneously, and therefore offer functionality that is quite similar to a touchscreen, albeit with different movement semantics because of their physical separation from the screen (discussed below).

VR Controllers

VR controllers (and other similar devices like the Wiimote from the Nintendo Wii) allow users to point at objects in a three-dimensional virtual world by moving a real-world controller and “projecting” the controller’s position into the virtual space. They often also include sensors to detect the yaw, pitch, and roll of the sensors. There are often other inputs in the controller device, like analog sticks and buttons.

Hand Tracking

Devices like the Apple Vision (introduced during the time this document was being written) and (to a lesser extent) the Meta Quest have the ability to track the wearer’s hand and directly interpret gestures and movements as input. As the human hand can assume a staggering number of orientations and configurations, a finite list of specific shapes and movements must be identified and labelled to allow for clear software-user interaction.

Mouse

The Buxton Three-State Model

Bill Buxton, an early pioneer in the field of human-computer interaction, came up with a three-state model for pointing devices; a device can be “Out of Range”, “Tracking”, or “Dragging”. Not all devices support all three states, and some devices have multiple actuators that can have the three-state model individually applied.

stateDiagram-v2

direction LR

state "State 0" as s0

state "State 1" as s1

state "State 2" as s2

s0 --> s0 : Out Of Range

s1 --> s1 : Tracking

s2 --> s2 : Dragging

s0 --> s1 : Stylus On

s1 --> s0 : Stylus Lift

s1 --> s2 : Tip Switch Close

s2 --> s1 : Tip Switch Open

For demonstration, here is the model applied to a few devices:

Computer Mouse

A mouse is never in the “Out of Range” state. Even though it can technically be lifted off its surface, the mouse does not report this as a separate condition; instead, it behaves as-if it is stationary until it can once again sense the surface moving underneath.

The remaining two states apply to each button individually; when a button is not being pressed, the mouse is considered in the “tracking” state with respect to that button. When a button is held down, the mouse is “dragging” with respect to that button. A “click” is simply considered a zero-length drag under this model.

In the case of a two-button mouse, this means that the mouse can be in a total of 4 different states: tracking, left button dragging, right button dragging, and two-button dragging. In practice, very little software actually does anything meaningful with two-button dragging.

Touch Screen

Applying the model to a touch screen, one can observe that current hardware has no way to sense that a finger that is “hovering, but not quite making contact with the screen”. This means that the “Tracking” state can be ruled out, leaving only the “Out of Range” and “Dragging” states. Since many touch screens can support multiple fingers touching the screen concurrently, and each finger can be in one of two states, there are potentially 2^N different “states” that a touchscreen can be in. Windows assigns meaning to many two, three, and four-finger gestures.

Tablet Digitizer

A tablet digitizer supports all three states: when the stylus is far away from the surface, it is considered “out of range”; when it is located slightly above the surface, it is “tracking”; and when it is making contact with the surface, it is “dragging”.

The W3C standards for pointing devices are based on this three-state model, but applied to each individual web element instead of the entire system. This makes things like “Out-of-Range” possible for the mouse, since it can be out of range of a web element.

The W3C uses the terms “over” and “out” to convey the transition between “out-of-range” and “tracking” (which the W3C calls “hover”), and the terms “down” and “up” convey the transition between “tracking” and “dragging”.

The standard also address some of the known shortcomings of the model to improve portability and consistency; these improvements will be discussed more below.

The Windows Pointer API is supposedly based around this model, but unfortunately real-world testing shows that the model is not followed very consistently with respect to the actual signals sent to the application.

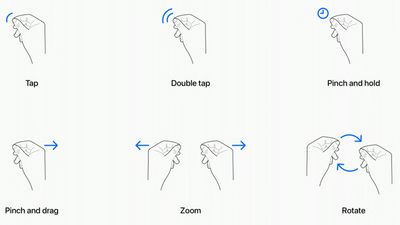

Gestures

In contrast to the sort-of “anything goes” UI designs of the past, modern operating systems like Windows, Mac OS X, iOS, Android, and even modern Linux DEs have an “opinionated” idea of how user interaction should behave across all apps on the platform (the so-called “look and feel” of the operating system).

Users expect gestures like swipes, pinches, and taps to act the same way across all apps for a given operating system, and they expect things like on-screen keyboards or handwriting recognition to pop up in certain contexts. Failing to meet those expectations makes an app look less polished, and (especially as far as accessibility is concerned) it frustrates the user and makes it more difficult for them to interact with the app.

Microsoft defines guidelines for various behaviours that Windows applications should ideally adhere to in the Input and Interactions section on MSDN. Some of these are summarized quickly below:

Drag and Drop

Drag and drop allows a user to transfer data from one application to another. The gesture begins when a pointer device moves into the “Dragging” state over top of a UI element, usually as a result of holding down a mouse button or pressing a finger on a touchscreen. The user moves the pointer over top of the receiver of the data, and then ends the gesture by releasing the mouse button or lifting their finger off the touchscreen. Window interprets this transition out of the “Dragging” state as permission to initiate the data transfer.

Firefox has supported Drag and Drop for a very long time, so it will not be discussed further.

Pan and Zoom

When using touchscreens (and multi-touch touchpads), users expect to be able to cause the viewport to “pan” left/right/up/down by pressing two fingers on the screen (creating two pointers in “Dragging” state) and moving their fingers in the direction of movement. When they are done, they can release both fingers (changing both pointers to “Out of Bounds”).

A zoom can be signalled by moving the two fingers apart or together in a “pinch” or “reverse pinch” gesture.

Single Pointer Panning

Applications that are based on a UI model of the user interacting with a “page” often allow a single pointer “Dragging” over the viewport to cause the viewport to pan, similarly to the two-finger panning discussed in the previous section.

Note that this gesture is not as universal as two-finger panning is – as a counterexample, graphics programs tend to treat one-finger dragging as object manipulation and two-finger dragging as viewport panning.

Inertia

When a user is done panning, they may lift their finger/pen off the screen while the viewport is still in motion. Users expect that the page will continue to move for a little while, as-if the user had “tossed” the page when they let go. Effectively, the page behaves as though it has “momentum” that needs to be gradually lost before the page comes to a full stop.

Modern operating systems provide this behavior via their various native widget toolkits, and the curve that objects follow as they slow to a stop are different across OSes. In that way, they can be considered part of the unique “look and feel” of the OS. Users expect the scrolling of pages in their web browser to behave this way, and so when Firefox fails to provide this behavior it can be jarring.

Overscroll and Elastic Bounce

When a user is panning the page and reaches the outer edges, Microsoft recommends that the app should begin an “elastic bounce” animation, where the page will allow the user to scroll past the end (“overscroll”), show empty space underneath the page, and then sort of “snap back” like a rubber band that’s been stretched and then released. You can see a demonstration in this article, which discusses Microsoft adding it to Chromium.

History of Web Standards and Windows APIs

The World-Wide Web Consortium (W3C) and the Web Hypertext Application Technology Working Group (WHATWG) manage the standards that detail the interface between a user agent (like Firefox) and applications designed to run on the Web Platform. The user agent, in turn, must rely on the operating system (Windows, in this case) to provide the necessary APIs to implement the standards required by the Web Platform.

As a result of that relationship, a Web Standard is unlikely to be created until all widely-used operating systems provide the required APIs. That allows us to build a linear timeline with a predictable pattern: a new type of device becomes popular, the APIs to support it are introduced into operating systems, and eventually a cross-platform standard is introduced into the Web Platform.

The following sections detail the history of input devices supported by Windows and the Web Platform:

1985 - Computer Mouse Support (Windows 1.0)

The first version of Windows (1985) supported a computer mouse. Support for other input devices is not well-documented, but probably non-existant.

1991 - Third-Party De-facto Pen Support (Wintab)

In the late 80s and early 90s, any tablet pen hardware vendor that wanted to support Windows would need to write a device driver and design a proprietary user-mode API to expose the device to user applications. In turn, application developers would have to write and maintain code to support the APIs of every relevant device vendor.

In 1991, a company named LCS/Telegraphics released an API for Windows called “Wintab”, which was designed in collaboration with hardware and software vendors to define a general API that could be targetted by device drivers and applications.

It would take Microsoft more than a decade to include first-party support for tablet pens in Windows, which allowed Wintab to become the de-facto standard for pen support on Windows. The Wintab API continues to be supported by virtually all artist tablets to this day. Notable companies include Wacom, Huion, XP-Pen, etc.

1992 - Early Windows Pen Support (Windows for Pen Computing)

The earliest Windows operating system to support non-mouse pointing devices was Windows 3.1 with the “Windows for Pen Computing” add-on (1992). (For the curious, and I’m certain this book is a must-read!). Pen support was mostly implemented by translating actions into the existing

WM_MOUSExxxmessages, but also “upgraded” any application’sEDITcontrols intoHEDITcontrols, which looked the same but were capable of being handwritten into using a pen. This was not very user-friendly, as the controls stayed the same size and the UI was not adapted to the input method. This add-on never achieved much popularity.It is not documented whether Netscape Navigator (the ancestor of Mozilla Firefox) supported this add-on or not, but there is no trace of it in modern Firefox code.

1995 - Introduction of JavaScript and Mouse Events (De-facto Web Standard)

The introduction of JavaScript in 1995 by Netscape Communications added a programmable, event-driven scripting environment to the Web Platform. Browser vendors quickly added the ability for scripts to listen for and react to mouse events. These are the well-known events like

mouseover,mouseenter,mousedown, etc. that are ubiquitous on the web, and are known by basically anyone who has ever written front-end JavaScript.This ubiquity created a de-facto standard for mouse input, which would eventually be formally standardized by the W3C in the HTML Living Standard in 2001.

The Mouse Event APIs assume that the computer has one single pointing device which is always present, has a single cursor capable of “hovering” over an element, and has between one and three buttons.

When support for other pointing devices like touchscreen and pen first became available in operating systems, it was exposed to the web by interpreting user actions into equivalent mouse events. Unfortunately, this is unable to handle multiple concurrent pointers (like one would get from multitouch screens) or report the kind of rich information a pen digitizer can provide, like tilt angle, pressure, etc. This eventually lead the W3C to develop the new “Touch Events” standard to expose touch functionality, and eventually the “Pointer Events” to expose more of the rich information provided by pens.

2005 - Mainstream Pen Support (Windows XP Tablet PC Edition)

It was the release of Windows XP Tablet PC Edition (2005) that allowed Windows applications to directly support tablet pens by using the new COM “Windows Tablet PC” APIs, most of which are provided through the main InkCollector class. The

InkCollectorfunctionality would eventually be “mainlined” into Windows XP Professional Service Pack 2, and continues to exist in modern Windows releases.The Tablet PC APIs consist of a large group of COM objects that work together to facilitate enumerating attached pens, detecting pen movement and pen strokes, and analyzing them to provide:

Cursor Movement: translates the movements of the pen into the standard mouse events that applications expect from mouse cursor movement, namely

WM_NCHITTEST,WM_SETCURSORandWM_MOUSEMOVE.Gesture Recognition: detects common user actions, like “tap”, “double-tap”, “press-and-hold”, and “drag”. The InkCollector delivers these events via COM SystemGesture events using the InkSystemGesture enumeration. It will also translate them into common Win32 messages; for example, a “drag” gesture would be translated into a

WM_LBUTTONDOWNmessage, severalWM_MOUSEMOVEmessages, and finally aWM_LBUTTONUPmessage.An application that is using

InkCollectorwill receive both types of messages: traditional mouse input through the Win32 message queue, and “Tablet PC API” events through COM callbacks. It is up to the application to determine which events matter to it in a given context, as the two types of events are not guaranteed by Microsoft to correspond in any predictable way.Shape and Text Recognition: allows the app to recognize letters, numbers, punctuation, and other common shapes the user might make using their pen. Supported shapes include circles, squares, arrows, and motions like “scratch out” to correct a misspelled word. Custom recognizers exist that allow recognition of other symbols, like music notes or mathematical notation.

Flick Recognition: allows the user to invoke actions via quick, linear motions that are recognized by Windows and sent to the app as

WM_TABLET_FLICKmessages. The app can choose to handle the window message or pass it on to the default window procedure, which will translate it to scrolling messages or mouse messages.For example, a quick upward ‘flick’ corresponds to “Page up”, and a quick sideways flick in a web browser would be “back”. Flicks were never widely used by Windows apps, and they may have been removed in more recent versions of Windows, as the existing Control Panel menus for configuring them seem to no longer exist as of Windows 10 22H2.

Firefox does not appear to have ever used these APIs to allow tablet pen input, with the exception of one piece of code to detect when the pen leaves the Firefox window to solve Bug 1016232.

2009 - Touch Support: WM_GESTURE (Windows 7)

While attempts were made with the release of Windows Vista (2007) to support touchscreens through the existing tablet APIs, it was ultimately the release of Windows 7 (2009) that brought first-class support for Touchscreen devices to Windows with new Win32 APIs and two main window messages:

WM_TOUCHandWM_GESTURE.These two messages are mutually-exclusive, and all applications are initially set to receive only

WM_GESTUREmessages. Under this configuration, Windows will attempt to recognize specific movements on a touch digitizer and post “gesture” messages to the application’s message queue. These gestures are similar to (but, somewhat-confusingly, not identical to) the gestures provided by the “Windows Tablet PC” APIs mentioned above. The main gesture messages are: zoom, pan, rotate, two-finger-tap, and press-and-tap (one finger presses, another finger quickly taps the screen).In contrast to the behavior of the

InkCollectorAPIs, which will send both gesture events and translated mouse messages, theWM_GESTUREmessage is truly “upstream” of the translated mouse messages; the translated mouse messages will only be generated if the application forwards theWM_GESTUREmessage to the default window procedure. This makes programming against this API simpler than theInkCollectorAPI, as there is no need to state-fully “remember” that an action has already been serviced by one codepath and needs to be ignored by the other.Firefox current supports the

WM_GESTUREmessage when Asynchronous Pan and Zoom (APZ) is not enabled (although we do not handle inertia in this case, so the page comes to a dead-stop immediately when the user stops scrolling).

2009 - Touch Support: WM_TOUCH (Windows 7)

Also introduced in Windows 7, an application that needs full control over touchscreen events can use RegisterTouchWindow to change any of its windows to receive

WM_TOUCHmessages instead of the more high-levelWM_GESTUREmessages. These messages explicitly notify the application about every finger that contacts or breaks contact with the digitizer (as well as each finger’s movement over time). This provides absolute control over touch interpretation, but also means that the burden of handling touch behavior falls completely on the application.To help ease this burden, Microsoft provides two COM APIs to interpret touch messages,

IManipulationProcessorandIInertiaProcessor.

IManipulationProcessorcan be considered a superset of the functionality available through normal gestures. The application feedsWM_TOUCHdata into it (along with other state, such as pivot points and timestamps), and it allows for manipulations like: two-finger rotation around a pivot, single-finger rotation around a pivot, simultaneous rotation and translation (for example, ‘dragging’ a single corner of a square). These MSDN diagrams give a good overview of the kinds of advanced manipulations an app might support.

IInertiaProcessorworks withIManipulationProcessorto add inertia to objects in a standard way across the operating system. It is likely that later APIs that provide this (like DirectManipulation) are using these COM objects under the hood to accomplish their inertia handling.Firefox currently handles the

WM_TOUCHevent when Asynchronous Pan and Zoom (APZ) is enabled, but we do not use either theIInertiaProcessornor theIManipulationProcessor.

2012 - Unified Pointer API (Windows 8)

Windows 8 (2012) was Microsoft’s initial attempt to make a touch-first, mobile-first operating system that (ideally) would make it easy for app developers to treat touch, pen, and mouse as first-class input devices.

By this point, the Windows Tablet APIs would allow tablet pens to draw text and shapes like squares, triangles, and music notes, and those shapes would be recognizable by the Windows Ink subsystem.

At the same time, Windows Touch allowed touchscreens to have advanced manipulation, like rotate + translate, or simultaneous pan and zoom, and it allowed objects manipulated by touch to have momentum and angular velocity.

The shortcomings of having separate input stacks for these various devices starts to be become apparent after a while: Why shouldn’t a touchscreen be able to recognize a circle or a triangle? Why shouldn’t a pen be able to have complex rotation and zoom functionality? How do we handle these newer laptop touchpads that are starting to handle multi-touch gestures like a touchscreen, but still cause relative cursor movement like a mouse? Why does my program have to have 3 separate codepaths for different pointing devices that are all very similar?

The Windows Pointer Device Input Stack introduces new APIs and window messages that generalize the various types of pointing devices under a single API while still falling back to the legacy touch and tablet input stacks in the event that the API is unused. (Note that the touch and tablet stacks themselves fall back to the traditional mouse input stack when they are unused.)

Microsoft based their pointer APIs off the Buxton Three-State Model (discussed earlier), where changes between “Out-of-Range” and “Tracking” are signalled by

WM_POINTERENTERANDWM_POINTERLEAVEmessages, and changes between “Tracking” and “Dragging” are signalled byWM_POINTERDOWNandWM_POINTERUP. Movement is indicated viaWM_POINTERUPDATEmessages.If these messages are unhandled (the message is forwarded to

DefWindowProc), the Win32 subsystem will translate them into touch or gesture messages. If unhandled, those will be further translated into mouse and system messages.While the Pointer API is not without some unfortunate pitfalls (which will be discussed later), it still provides several advantages over the previously available APIs: it can allow a mostly-unified codepath for handling pointing devices, it circumvents many of the often-complex interactions between the previous APIs, and it provides the ability to simulate pointing devices to help facilitate end-to-end automated testing.

Firefox currently uses the Pointer APIs to handle tablet stylus input only, while other input methods still use the historical mouse and touch input APIs above.

2013 - DirectManipulation (Windows 8.1)

DirectManipulation is a DirectX based API that was added during the release of Windows 8.1 (2013). This API allows an app to create a series of “viewports” inside a window and have scrollable content within each of these viewports. The manipulation engine will then take care of automatically reading Pointer API messages from the window’s event queue and generating pan and zoom events to be consumed by the app.

In the case that the app is also using DirectComposition to draw its window, DirectManipulation can pipe the events directly into it, causing the app to essentially get asynchronous pan and zoom with proper handling of inertia and overscroll with very little coding.

DirectManipulation is only used in Firefox to handle data coming from Precision Touchpads, as Microsoft provides no other convenient API for obtaining data from such devices. Firefox creates fake content inside of a fake viewport to capture the incoming events from the touchpad and translates them into the standard Asynchronous Pan and Zoom (APZ) events that the rest of the input pipeline uses.

2013 - Touch Events (Web Standard)

“Touch Events” became a W3C recommendation in October, 2013.

At this point, Microsoft’s first operating system to include touch support (Windows 7) was the most popular desktop operating system, and the ubiquity of smart phones brought a huge uptick in users with touchscreen inputs. All major browsers included some API that allowed reading touch input, prompting the W3C to formalize a new standard to ensure interoperability.

With the Touch Events API, multiple touch interactions may be reported simultaneously, each with their own separate identifier for tracking and their own coordinates within the screen, viewport, and client area. A touch is reported by: a

touchstartevent with a unique ID for each contact, zero-or-moretouchmoveevents with that ID, and finally atouchendevent to signal the end of that specific contact.The API also has some amount of support for pen styluses, but it lacks important features necessary to truly support them: hovering, pressure, tilt, or multiple cursors like an erasure. Ultimately, its functionality has been superceded by the newer “Pointer Events” API, discussed below.

2016 - Precision Touchpads (Windows 10)

Early touchpads emulated a computer mouse by directly using the same IBM PS/2 interface that most computer mice used and translating relative movement of the user’s finger into equivalent movements of a mouse on a surface.

As touchpad technology advanced and more powerful interface standards like USB begun to take over the consumer market, touchpad vendors started adding extra features to their hardware, like tap-to-click, tap-and-drag, and tap-and-hold (to simulate a right click). These behaviors were implemented by touchpad vendors either in hardware drivers and/or user mode “hooks” that injected equivalent Win32 messages into the appropriate target.

As expected, each touchpad vendor’s driver had its own subtly-different behavior from others, its own bugs, and its own negative interactions with other software.

During the later years of Windows 8, Microsoft and touchpad company Synaptics co-developed the “Precision Touchpad” standard, which defines an interface for touchpad hardware to report its physical measurements, precision, and sensor configuration to Windows and allows it to deliver raw touch data. Windows then interprets the data and generates gestures and window messages in a standard way, removing the burden of implementing these behaviors from the touchpad vendor and providing the OS with rich information about the user’s movements.

It wasn’t until the 2016 release of Windows 10 14946 that Microsoft would support all the standard gestures through the new standard. Although adoption by vendors has been a bit slow, the fact that it is a requirement for Windows 11 means that vendor support for this standard is imminent.

Unfortunately, there’s a piece of bad news: Microsoft did not implement the above “Unified Pointer API” for use with touchpads, as the developers of Blender discovered when they moved to the Pointer API. Instead, Microsoft expects developers to either use DirectManipulation to automatically get pan/zoom enabled for their app, or the RawInput API to directly read touchpad data.

2019 - Pointer Events (Web Standard)

“Pointer Events” became a level 2 W3C recommendation in April, 2019. They considered the work done by Microsoft as part of the design of their own Pointer API, and in many ways the W3C standard resembles an improved, better specified, more consistent, and easier-to-use version of the APIs provided by the Win32 subsystem.

The Pointer Events API generalizes devices like touchscreens, mice, tablet pens, VR controllers, etc. into a “thing that points”. A pointer has (optional) properties: a width and height (big for a finger, 1px for a mouse), an amount of pressure, a tilt angle relative to the surface, some buttons, etc. This helps applications maximize code reuse for handling pointer input by having a common codebase written against these generalized traits. If needed, the application may also have smaller, specialized sections of code for each concrete pointer type.

Certain types of pointers (like pens and touchscreens) have a behavior where they are always “captured” by the first object that they interact with. For example, if a user puts their finger on an empty part of a web page and starts to scroll, their finger is now “captured” by the web page itself. “Captured” means that even if their finger moves over an element in the web page, that element will not receive events from the finger – the page itself will until the entire interaction stops.

The events themselves very closely follow the Buxton Three-State Model (discussed earlier), where

pointerover/pointeroutmessages indicate transitions from “Out of Range” to “Tracking” and visa-versa, andpointerdown/pointerupmessages transition between “Tracking” and “Dragging”.pointermoveupdates the position of the pointer, and a specialpointercancelmessage is sent to inform the page that the browser is “cancelling” apointerdownevent because it has decided to consume it for a gesture or because the operating system cancelled the pointer for its own reasons.

CSS “interaction” Media Queries

(Note that this section is not about the pointer-events CSS property, which defines the circumstances where an element can be the target of pointer events.)

The W3C defines the interaction-related media queries in the Media Queries Level 4 - Interaction Media Features document.

To summarize, the main interaction-related CSS Media Queries that Firefox must

support are pointer, any-pointer, hover and any-hover.

pointer

Allows the webpage to query the existence of a pointing device on the machine, and (if available) the assumed “pointing accuracy” of the “primary” pointing device. The device considered “primary” on a machine with multiple input devices is a policy decision that must be made by the web browser; Windows simply provides the APIs to query information about attached devices.

The browser is expected to return one of three strings to this media query:

noneThere is no pointing device attached to the computer.

coarseThe primary pointing device is capable of approximately pointing at a relatively large target (like a finger on a touchscreen).

fineThe primary pointing device is capable of near-pixel-level accuracy (like a computer mouse or a tablet pen).

any-pointer

Similar to

pointer, but represents the union of capabilities of all pointers attached to the system, such that the meanings become:

noneThere is no pointing device attached to the computer.

coarseThere is at-least one “coarse” pointer attached.

fineThere is at-least one “fine” pointer attached.

hover

Allows the webpage to query whether the primary pointer is capable of “hovering” over top of elements on the page. Computer mice, touchpad cursors, and higher-end pen tablets all support this, whereas current touchscreens are “touch” or “no touch”, and they cannot detect a finger hovering over the screen.

hoverThe primary pointer is capable of reporting hovering.

noneThe primary pointer is not capable of reporting hovering.

any-hover

Indicates whether any pointer attached to the system has the

hovercapability.

Selection of the Primary Pointing Device

To illustrate the complexity of this topic, consider the Microsoft Surface Pro.

The Surface Pro has an advanced screen that is capable of receiving touch input, but it can also behave like a pen digitizer and receive input from a stylus with advanced pen capabilities, like hover sensing, pressure sensitivity, multiple buttons, and even multiple “tips” (a pen and eraser end).

In this case, what should Firefox consider the primary pointing device?

Perhaps the user intends to use their Surface Pro like a touchscreen tablet,

at which point Firefox should report pointer: coarse and hover: none

capabilities.

But what if, instead, the user wants to sketch art or take notes using a pen on

their Surface Pro? In this case, Firefox should be reporting pointer: fine

and hover: hover.

Imagine that the user then attaches the “keyboard + touchpad” cover attachment

to their Surface Pro; naturally, we will consider that the user’s intent is for

the touchpad to become the primary pointing device, and so it is fairly clear

that we should return pointer: fine and hover: hover in this state.

However, what if the user tucks the keyboard/touchpad attachment behind the tablet and begins exclusively operating the device with their finger?

This example shows that complex, multi-input machines can resist classification and blur the lines between labels like “touch device”, “laptop”, “drawing tablet”, etc. It also illustrates that identifying the “primary” pointing device using only machine configuration may yield unintuitive and suboptimal results.

While we can almost-certainly improve our hardware detection heuristics to better answer this question (and we should, at the very least), perhaps it makes more sense for Firefox to incorporate user intentions into the decision. Intentions could be communicated directly by the user through some sort of setting or indirectly through the user’s actions.

For example, if the user intends to draw on the screen with a pen, perhaps Firefox provides something like a “drawing mode” that the user can toggle to change the primary pointing device to the pen. Or perhaps it’s better for Firefox to interpret the mere fact of receiving pen input as evidence of the user’s intent and switch the reported primary pointing device automatically.

If we wanted to switch automatically, there are predictable traps and pitfalls we need to think about: we need to ensure that we don’t create frustrating user experiences where web pages may “pop” beneath the user suddenly, and we should likely incorporate some kind of “settling time” so we don’t oscillate between devices.

It’s worth noting that Chromium doesn’t seem to incorporate anything like what’s being suggested here, so if this is well-designed it may be an opportunity for Firefox to try something novel.

State of the Browser

Pan and Zoom, Inertia, Overscroll, and Elastic Bounce

As can be seen in the videos below, Firefox’s support for inertia, overscroll, and elastic bounce works well on all platforms when a stylus pen is used as the input device, and it also works just fine with the touchscreen on the Dell XPS 15. However, it completely fails when the touchscreen is used on the Microsoft Surface Pro. While more investigation is needed to completely understand these issues, the fact that the correctly-behaving digitizing pens use the Pointer API and the misbehaving input devices do not may be related.

Pointer Media Queries

“any-pointer” Queries

Unlike the pointer media queries, which rely on the browser to make a policy

decision about what should be considered the “primary” pointer in a given

system configuration, the any-pointer queries are much more objective and

binary: the computer either has a type of device attached to it, or it

doesn’t.

any-pointer: coarse

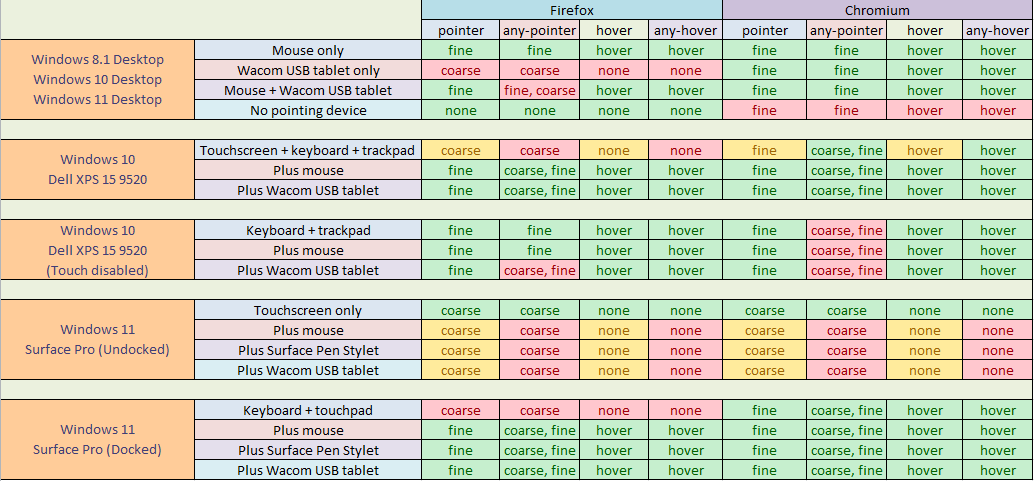

Firefox reports that there are “coarse” pointing devices present if either of these two points is true:

GetSystemMetrics(SM_DIGITIZER)reports that a device that supports touch or pen is present.Based on heuristics, Firefox concludes that it is running on a computer it considers a “tablet”.

Point #1 is incorrect, as a pen is not a “coarse” pointing device. Note that this is a recent regression in Bug 1811303 that was uplifted to Firefox 112, so this actually regressed as this document was being written! This is responsible for the incorrect “Windows 10 Desktop + Wacom USB Tablet” issue in the table.

Point #2 is a clear case of the XY Problem, where Firefox is trying to determine if a coarse pointing device is present by determining whether it is running on a tablet, when instead it should be directly testing for coarse pointing devices (since, of course, those can exist on machines that wouldn’t normally be considered a “tablet”). This is responsible for the incorrect “Windows 10 Dell XPS 15 (Touch Disabled) + Wacom USB Tablet” issue in the table below.

any-pointer: fine

Firefox reports that there are “fine” pointing devices present if and only if it detects a mouse. This is clearly already wrong. Firefox determines that the computer has a mouse using the following algorithm:

If

GetSystemMetrics(SM_MOUSEPRESENT)returns false, report no mouse.If Firefox does not consider the current computer to be a tablet, report a mouse if there is at-least one “mouse” device driver running on the computer.

If Firefox considers the current computer to be a tablet or a touch system, only report a mouse if there are at-least two “mouse” device drivers running. This exists because some tablet pens and touch digitizers report themselves as computer mice.

This algorithm also suffers from the XY problem – Firefox is trying to determine whether a fine pointing device exists by determining if there is a computer mouse present, when instead it should be directly testing for fine pointing devices, since mice are not the only fine pointing devices.

Because of this proxy question, this algorithm is completely dependent on any attached fine pointing device (like a pen tablet) to report itself as a mouse. Point #3 makes the problem even worse, because if a computer that resembles a tablet fails to report its digitizers as mice, the algorithm will completely ignore an actual computer mouse attached to the system because it expects two of them to be reported!

Unfortunately, the Surface Pro has both a pen digitizer and a touch digitizer, and it reports neither as a mouse. As a result, this algorithm completely falls apart on the Surface Pro, failing to report any “fine” pointing device even when a computer mouse is plugged in, a pen is plugged in, or even when the tablet is docked because its touchpad is only one mouse and it expects at least two.

This is also responsible for failing to report the trackpad on the Dell XPS 15 as “fine”, because the Dell XPS 15 has a touchscreen and therefore looks like a “tablet”, but doesn’t report 2 mouse drivers.

any-pointer: hover

Firefox reports that any device that is a “fine” pointer also supports “hover”, which does generally hold true, but isn’t necessarily true for lower-end pens that only support tapping. It would be better for Firefox to directly query the operating system instead of just assuming.

“pointer” media query

As discussed previously at length, this media query relies on a “primary” designation made by the browser. Below is the current algorithm used to determine this:

If the computer is considered a “tablet” (see below), report primary pointer as “coarse” (this is clearly already the wrong behavior).

Otherwise, if the computer has a mouse plugged in, report “fine”.

Otherwise, if the computer has a touchscreen or pen digitizer, report “coarse” (this is wrong in the case of the digitizer).

Otherwise, report “fine” (this is wrong; should report “None”).

Firefox uses the following algorithm to determine if the computer is a “tablet” for point #1 above:

It is not a tablet if it’s not at-least running Windows 8.

If Windows “Tablet Mode” is enabled, it is a tablet no matter what.

If no touch-capable digitizers are attached, it is not a tablet.

If the system doesn’t support auto-rotation, perhaps because it has no rotation sensor, or perhaps because it’s docked and operating in “laptop mode” where rotation won’t happen, it’s not a tablet.

If the vendor that made the computer reports to Windows that it supports “convertible slate mode” and it is currently operating in “slate mode”, it’s a tablet.

Otherwise, it’s not a tablet.

Table with comparison to Chromium

The following table shows how Firefox and Chromium respond to various pointer queries. The “any-pointer” and “any-hover” columns are not subjective and therefore are always either green or red to indicate “pass” or “fail”, but the “pointer” and “hover” may also be yellow to indicate that it’s “open to interpretation” because of the aforementioned difficulty in determining the “primary pointer”.

Related Bugs

Bug 1813979 - For Surface Pro media query “any-pointer: fine” is true only when both the Type Cover and mouse are connected

Bug 1747942 - Incorrect CSS media query matches for pointer, any-pointer, hover and any-hover on Surface Laptop

Bug 1528441 - @media (hover) and (any-hover) does not work on Firefox 64/65 where certain dual inputs are present

Bug 1697294 - Content processes unable to detect Windows 10 Tablet Mode

Bug 1806259 - CSS media queries wrongly detect a Win10 desktop computer with a mouse and a touchscreen, as a device with no mouse (hover: none) and a touchscreen (pointer: coarse)

Web Events

The pen stylus worked well on all tested systems – The correct pointer events were fired in the correct order, and mouse events were properly simulated in case the default behavior was allowed.

The touchscreen input was less reliable. On the Dell XPS 15, the

“Pointer Events” were flawless, but the “Touch Events” were missing

an important step: the touchstart and touchmove messages were sent just

fine, but Firefox never sends the touchend message! (Hopefully that isn’t

too difficult to fix!)

Unfortunately, everything really falls apart on the Surface Pro using the

touchscreen – neither the “Pointer Events” nor the “Touch Events” fire at all!

Instead, the touch is completely absorbed by pan and zoom gestures, and nothing

is sent to the web page. The website’s request for touch-action: none is

ignored, and the web page is never given any opportunity to call

Event.preventDefault() to cancel the pan/zoom behavior.

Operating System Interfaces

As was discussed above, Windows has multiple input APIs that were each introduced in newer version of Windows to handle devices that were not well-served by existing APIs.

Backward compatibility with applications designed against older APIs is

realized when applications call the default event handler (DefWindowProc)

upon receiving an event type that they don’t recognize (which is what apps have

always been instructed to do if they receive events they don’t recognize).

The unrecognized newer events will be translated by the default event handler

into older events and sent back to the application. A very old application may

have this process repeat through several generations of APIs until it finally

sees events that it recognizes.

Firefox currently uses a mix of the older and newer APIs, which complicates the input handling logic and may be responsible for some of the difficult-to-explain bugs that we see reported by users.

Here is an explanation of the codepaths Firefox uses to handle pointer input:

Firefox handles the

WM_POINTER[LEAVE|DOWN|UP|UPDATE]messages if the input device is a tablet pen and an Asynchronous Pan and Zoom (APZ) compositor is available. Note that this already may not be ideal, as Microsoft warns (here) that handling some pointer messages and passing other pointer messages toDefWindowProchas unspecified behavior (meaning that Win32 may do something unexpected or nonsensical).If the above criteria aren’t met, Firefox will call

DefWindowProc, which will re-post the pointer messages as either touch messages or mouse messages.If DirectManipulation is being used for APZ, it will output the

WM_POINTERCAPTURECHANGEDif it detects a pan or zoom gesture it can handle. It will then handle the rest of the gesture itself.DirectManipulation is used for all top-level and popup windows as long as it isn’t disabled via the

apz.allow_zoomingorapz.windows.force_disable_direct_manipulationprefs.If the pointing device is touch, the next action depends on whether an Asynchronous Pan and Zoom (APZ) compositor is available. If it is, the window will have been registered using

RegisterTouchWindow, and Firefox will receiveWM_TOUCHmessages, which will be sent to the “Touch Event” API and handled directly by the APZ compositor.If there is no APZ compositor, it will instead be received as a

WM_GESTUREmessage or a mouse message, depending on the movement. Note that these will be more basic gestures, like tap-and-hold.If none of the above apply, the message will be converted into standard

WM_MOUSExxxmessages via a call toDefWindowProc.

Discussion

Here is where some of the outstanding thoughts or questions can be listed. This can be updated as more questions come about and (hopefully) as answers to questions become apparent.

CSS “pointer” Media Queries

The logic for the

any-pointerandany-hoverqueries are objectively incorrect and should be rewritten altogether. That is not as big of a job as it sounds, as the code is fairly straightforward and self-contained. (Note: Improvements have already been made in Bug 1813979)There are a few behaviors for

pointerandhoverthat are objectively wrong (such as reporting acoarsepointer when the Surface Pro is docked with a touchpad). Those should be fixable with a code change similar to the previous bullet.Do we want to continue to use only machine configuration to decide what the “primary” pointer is, or do we also want to incorporate user intent into the algorithm? Or, alternatively:

Do we create a way for the user to override? For example, a “Drawing Mode” button if a tablet digitizer is sensed.

Do we attempt to change automatically in response to user action?

An example was used above of a docked Surface Pro computer, where the user may use the keyboard and touchpad for a while, then perhaps tuck that behind and use the device as a touchscreen, and then perhaps draw on it with a tablet stylus.

We would need to be careful to avoid careless “popping” or “oscillating” if we react too quickly to changing input types.

On a separate-but-related note, the W3C suggested that it might be beneficial to allow users to at-least disable all reporting of

finepointing devices for users who may have a disability that prevents them from being able to click small objects, even with a fine pointing device.

Pan-and-Zoom, Inertia, Overscroll, and Elastic Bounce

Inertia, overscroll, and elastic bounce are just plain broken on the Surface Pro. That should definitely be investigated.

We can see from the video below that Microsoft Edge has quite a bit more overscroll and a more elastic bounce than Firefox does, and it also allows elastic bounce in directions that the page itself doesn’t scroll.

Edge’s way seems more similar to the user experience I’d expect from using Firefox on an iPhone or Android device. Perhaps we should consider following suit?

Web Events

It’s worth investigating why the

touchendmessage never seems to be sent by Firefox on any tested devices.It’s very disappointing that neither the Pointer Events API nor the Touch Events API works at all on Firefox on the Surface Pro. That should be investigated very soon!

Operating System Interfaces

With the upcoming sun-setting of Windows 7 support, Firefox has an opportunity to revisit the implementation of our input handling and try to simplify our codepaths and eliminate some of the workarounds that exist to handle some of these complex interactions, as well as fix entire classes of bugs - both reported and unreported - that currently exist as a result.

Does it make sense to combine the touchscreen and pen handling together and use the

WM_POINTERXXXmessages for both?This would eliminate the need to handle the

WM_TOUCHandWM_GESTUREmessages at all.Note that there is precedent for this, as GTK has already done so. It appears that Blender has plans to move toward this as well.

Tablet pens seemed to do very well in most of the testing, and they are also the part of the code that mainly exercises the

WM_POINTERXXXcodepaths. That may imply increased reliability in that codepath?The Pointer APIs also have good device simulation for integration testing.

Would we also want to roll mouse handling into it using the EnableMouseInPointer <https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/api/winuser/nf-winuser-enablemouseinpointer> __ call? That would allow us to also get rid of handling

WM_MOUSE[MOVE/WHEEL/HWHEEL]andWM_[LRM]BUTTON[UP|DOWN]messages. Truly one codepath (with a few minor branches) to rule them all!Nick Rishel sent this link that details the troubles that the developers of The Witness (a video game) ran into when using the

WM_TOUCHAPI. It argues that the API is poorly-designed, and advises that if Windows 7 support is not needed, the API should be avoided.

Should we exclusively use DirectManipulation for Pan/Zoom?

Multitouch touchpads bypass all of the

WM_POINTERmachinery for anything gesture-related and directly send their messages to DirectManipulation. We then “capture” all the DirectManipulation events and pump them into our events pipeline, as explained above.DirectManipulation also handles “overscroll + elastic bounce” in a way that aligns with Windows look-and-feel.

Perhaps it makes sense to just use DirectManipulation for all APZ handling and eliminate any attempt at handling this through other codepaths.

High-Frequency Input

“High-Frequency Input” refers to the ability for an app to be able to still perceive input events despite them happening at a rate faster than the app itself actually handles them.

Consider a mouse that moves through several points: “A->B->C->D->E”. If the application processes input when the mouse is at “A” and doesn’t poll again until the mouse is at point “E”, the default behavior of all modern operating systems is to “coalesce” these events and simply report “A->E”. This is fine for the majority of use cases, but certain workloads (such as digital handwriting and video games) can benefit from knowing the complete path that was taken to get from the start point to the end point.

Generally, solutions to this involve the operating system keeping a history of pointer movements that can be retrieved through an API. For example, Android provides the MotionEvent API that batches historal movements.

Unfortunately, the APIs to do this in Windows are terribly broken. As this blog makes clear, GetMouseMovePointsEx has so many issues that they had to remove its usage from their program because of the burden. That same blog entry also details that the newer Pointer API has the GetPointerInfoHistory that is supposed to support tracking pointer history, but it only ever tracks a single entry!

Perhaps luckily, there is currently no web standard for high-frequency input, although it has been asked about in the past.

If such a standard was ever created, it would likely be very difficult for Firefox on Windows to support it.

DirectManipulation and Pens

This is a todo item, but it needs to be investigated whether or not DirectManipulation can directly scoop up pen input, or whether it has to be handled by the application (and forwarded to DM if desired).